The expansion of Buddhism along Asia resulted in the introduction of Indic elements in several East Asian and Southeast Asian countries. Worship of Indian deities spread, and many of them took on different shades to meld with the different cultures of which they became a part.

Tara is one of the primary deities of Buddhism, although she likely has Hindu origins. In Puranic literature, dating to around the 4th century C.E, she is described as the goddess of navigation, responsible for the safety of ships at sea. Her devotees consisted of seafarers and boatmen. In Buddhism, she takes on a larger role: as a Mother Goddess, as a Bodhisattva, as a goddess of enlightenment. Her domain of seafaring was pushed to the back, but not abandoned entirely. Maritime travel was becoming increasingly common from the 6th century C.E, especially among Buddhists, and her worship increased along the Western and Eastern Coasts of India, Sri Lanka, Maldives, and Southeast Asia. In her Ashtamahabhaya form, she is the Protectress of Eight Great Perils, one of them being shipwrecks.

The Goddess Tara is depicted here in her Ashtamahabhaya Form

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Regmi, Jagdish Chandra: Goddess Tara: A Short Study; https://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk

Acri, Andrea: “Buddhism and Maritime Trade”; Maritime Buddhism; Oxford Research Encyclopedia; 20th Dec 2018

Maritime Buddhism | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion

Pattanaik, Devdutt: Avalokiteshvara, saviour of the sea merchant; The Hindu; 15th Feb 2024 https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/devdutt-pattanaik-column-avalokiteshvara-saviour-of-sea-merchant/article67837445.ece

Buddhist deities such as Avalokiteshwara and Mahapratisara—who share a similar domain with Tara—were invoked in times of storms while out at sea. Although they did not have a specific maritime connection like Tara, their status as protectors resulted in their names being mentioned in several maritime travelogues and biographies of Buddhist monks.

Saraswati is the Hindu goddess of knowledge and learning. Her origins can be traced to the Rigveda, where she was the personification of the river Saraswati. She was, in her earliest depictions, a goddess purely of water. She was associated with the abundance of her river, and its regular flooding. Her connection to speech, and then learning was a result of ritual chanting conducted on the banks of the river. Both Tara and Saraswati are often conflated with each other, on account of their similar connections to wisdom, compassion and learning. One of Tara’s warrior forms is known as Nila Saraswati, who also imparts knowledge.

Though a minor goddess during the Vedic period, by the rise of Buddhism, she had become increasingly popular. She is praised in the Mahayana Buddhist Text: Suvarna Prabhasa Sutra (Golden Light Sutra), wherein she has an entire chapter dedicated to her. It was through this text that her worship was introduced to East Asia with the spread of Mahayana Buddhism. In China, Saraswati was known as Da Biantianshen or Da Biantian, meaning Great Eloquence Deity. In Japan, this name transformed into Benzaiten and Benten. Her worship was more popular in Japan than in China, and so, we see a greater transformation taking place in the case of Benzaiten.

In appearance and domain, Benzaiten is very similar to Saraswati. The two are often portrayed as holding a stringed instrument: the veena for Saraswati and the biwa for Benzaiten. They also have an eight-armed warrior form (which finds its mention in the Golden Light Sutra) given their duty of protecting the Sutra, and by extension, Buddhists. They are both associated with knowledge, music, learning, art, as well as water.

Acri, Andrea: “Buddhism and Maritime Trade”; Maritime Buddhism; Oxford Research Encyclopedia; 20th Dec 2018

Maritime Buddhism | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion

Ludvik, Catherine: From Sarasvatī to Benzaiten; National Library of Canada; 2001; pp 10-12

Dokras, Uday: The River Saraswati and the Goddess Tara in Buddhism and Hinduism; Academia; p. 4 (PDF) The river Saraswati and the Goddess Tara in Buddhism and Hinduism | Dr. Uday Dokras – Academia.edu

Ludvik, Catherine: From Sarasvatī to Benzaiten; 2001; p. 228

“Chapter 15: The Great Goddess Sarasvati” The Sūtra of the Sublime Golden Light; Translated by Peter Alan Roberts and team; 84000:Translating the Words of the Buddha; 2023; Verse 15.90 https://read.84000.co/translation/toh555.html#UT22084-089-012-chapter-15

The Goddess Benzaiten is depicted here holding the biwa and sitting on a dragon

(Artist: Aoigaoka Keisei; Source: Wikimedia Commons)

While Saraswati’s connection to water is restricted to the river, Benzaiten’s domain includes water in all its forms, from river to lake to sea. Most of her shrines can be found near the coasts and waterbodies; the most famous one being on Enoshima, a small offshore island in the Sagami Bay, around 50 kilometres from Tokyo.

The tale of Enoshima is written in the Enoshima Engi, written in 1047 C.E, by Buddhist monk, Kokei. It describes the story of the five-headed dragon Gozuryu, who harassed the local people of the region. Benzaiten descended from the heavens, and caused the island of Enoshima to rise from the sea. The dragon asked her to wed him, but she refused on the account of his misdeeds. He resolved to work toward the betterment of the people , and today, Gozuryu and Benzaiten are both known as guardians of the island.

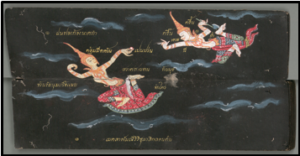

This scene depicts the battle between Moni Mekhala and Ream Eyso

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Juhl, Robert: “Introduction”; The Goddess, the Dragon, and the Island; 2016

https://web.archive.org/web/20161219073950/https://sites.google.com/site/bemsha10/intro

Juhl, Robert: “Translation Part 1-2”; The Goddess, the Dragon, and the Island; 2016;

https://web.archive.org/web/20161219073950/https://sites.google.com/site/bemsha10/intro

Kimball, Donny: The Legend of Enoshima: The Tale of Gozuryu and Benzaiten; A Different Side of Japan; 2016 https://donnykimball.com/enoshima-2f4a58d547ce

Manimekhala is another Hindu-Buddhist goddess, but unlike the others, the sea is fundamental to her domain. She is mentioned in the Tamil Buddhist epic, Manimekalai by Shattan, wherein she comes to the rescue of the titular character when she is being chased by a prince. The goddess whisks her across the sea, to the island of Manipallavam. She also finds mention in the Mahajanaka Jataka. Here too, in a manner similar to Manimekalai, she rescues the Bodhisattva Mahajanaka from a shipwreck.

She is more popular in Thailand and Cambodia, her depictions ranging from manuscript paintings to classical dances, widening her scope from a tertiary mythological figure to a full-fledged goddess. The Cambodian ritual dance tells the story of the goddess—locally called Moni Mekhala—and Ream Eyso. In pursuit of the crystal ball given to the goddess by their teacher, Ream Eyso threatened to kill her. Moni Mekhala gives him chase, and uses her crystal ball to blind Ream Eyso. This produces lightning, and the diamond axe Ream Eyso sends in retaliation produces thunder. Being a mythological representation of a thunderstorm, the dance is performed during New Year, marking the beginning of a new agricultural cycle. It is a shining example of a living tradition, and how a long-forgotten sea goddess from India lives on in the heritage of Cambodia.

It is the connection to water that makes the goddess, first of abundance, and then protection, as the water transforms from river to sea. This is seen especially in the case of Saraswati, when her earliest hymns celebrate her river’s abundance as bringing wealth. The domains of Tara and Manimekhala as sea goddesses put forth their characters as protector deities. Saraswati’s connection to might comes from her association with the storm gods, Maruts, in a manner paralleling Manimekhala’s role in creating a thunderstorm in her fight against Ream Eyso. In this way, Manimekhala too gains a connection to wealth and abundance. Thus, the importance of water ranges from prosperity to protection, from river to sea.

Manimekalai (The Dancer with the Magic Bowl); Translated by Alain Daniélou; New Directions; 1989; pp. 23-30

The Vedic Soul: Mahajanaka Jataka; WordPress

Candelario, Rosemary: Moni Mekhala and Ream Eyso, Edited by Prumsodun Ok (Review); Project Muse; 2014; pp. 324-325

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/542390

Ludvik, Catherine: From Sarasvatī to Benzaiten; National Library of Canada; 2001; p. 13

Ludvik, Catherine: From Sarasvatī to Benzaiten; National Library of Canada; 2001 pp. 18-20

0 Comments